To Live with It: Assessing an Accelerated Basic Writing Program from the Perspective of Teachers

Jason Evans

______________________________________________________________________________________________

ABSTRACT: At a community college in the Midwest, an English Department designs and implements a teacher-driven pilot project to experiment with its basic writing program. The article discusses some methods and the value of a local decision-making process that is driven primarily by the concerns of teachers and the experience of students.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

It has become common to see education in the United States in terms of a “crisis” that requires intervention. In higher education, one of the greatest perceived crises is the apparent mismatch between the academic skills possessed by many high school graduates and those required of college students. It seems like every week a new report surfaces in a national publication about remedial coursework in higher education. To take a few headlines in recent years from InsideHigherEd.com and the Chronicle of Higher Education:

“Colleges Need to Re-Mediate Remediation” (2009)

“Overkill on Remediation” (2012)

“Remedial Educators Warn of Misconceptions Fueling a Reform Movement” (2015)

“Passage Rates in Entry-Level Courses Drop at Florida’s Open-Admissions Colleges” (2016)

In a “national conversation” like this one about remediation, everyone seems to have something to say, from the mighty philanthropist to the lowly blogger and everyone in between.

For those of us who teach basic writing, this national attention comes as a mixed blessing. Suddenly there is real public focus on students who had been out of the higher education spotlight, those who, according to institutional processes in place for decades, have been deemed “not ready” for college coursework. Why, the public discourse asks, are colleges trying to drag these students through so many semesters of remedial classes? Isn’t there a faster, more economical way to credential our citizenry? When state funding for higher education dwindles, when legislatures cannot abide a tax hike and so press for cost-saving “innovations,” the pressure is on to do something, to try something. Basic writing faculty members who may have long toiled in the institutional shadows are suddenly blinking in the daylight as an administrator, herself responding to pressures from colleagues at other colleges or even from statewide organizations, urges them to innovate or have innovation done unto them.

Basic writing teachers thus have a warrant to exercise their institutional imagination, to experiment with course structures, to try things they’ve always wanted to do but which they haven’t had time or support to develop. This moment can be an opportunity to seize control and guide the local discourse, to enlist the administration on the side of right, and guide all down the path of enlightened change.

But that’s for those who innovate. For those who have innovation done unto them, the push comes often from an administrator, who is usually from another academic field and who has heard great things about such-and-such idea and wants to try it out. In these cases, the basic writing teacher is enlisted in (or subjected to) a reform project driven by the promise of better retention, stronger persistence, higher graduation rates, greater student success.

What is striking is how often these two paths converge on “acceleration”: basic writing teachers are attracted by co-requisite models because of the promise of higher student motivation, smaller class sizes, and better chances of students succeeding and coming back the next term to continue their studies; administrators and policymakers are attracted by the promise of increased course and program completion. Even if teachers and policymakers agree, it is still important that teachers and their concerns—How well are students learning? What helps students to thrive?—drive institutional changes.

I argue here that, when carrying out a project of institutional reform, it is best to create a local decision-making process that is driven primarily by the concerns of teachers and the experience of students. Much of the national discourse on basic skills instruction is obsessed with numbers on a large scale: how many students are “college ready,” how long it takes to earn a degree, how many more students would earn credentials if only they didn’t have to take basic math. Of course everyone welcomes positive quantitative trends, but we teachers should push back against tendencies to talk about education primarily as if it were machinery for credentialing workers. Instead we should assert the value of the rich, humane qualitative data known deeply and intimately by students and teachers: What is it like to be a person in this institutional setting? What is upbuilding and convivial, and what is a drag? What leads to learning and what stultifies?

These questions are not always at the forefront of educational change, but they should be. Teachers and their perspectives are important to assessment and evaluation in a number of ways. Throughout its 2016 annual policy platform, the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) recognizes how central teachers are to successful assessment practices: NCTE recommends “ensur[ing] teacher participation in the design or selection of assessments” and “that teachers are centrally involved in determining questions, assessment methods, and use of results that are valid for their disciplines and contexts” (2016 NCTE Education Policy Platform). Teachers are the experts, the professionals in the building with the most time and energy at stake in assessment, and for the results of the assessment to work for the students, teachers will have to assimilate any reforms or changes into their ways of doing their jobs. In a case study of institutional change in a secondary educational setting at a single school, Jason Margolis and Liza Nagel consider the kind of rapid, top-down changes often imposed on teachers in K-12 settings and the resistance produced in teachers in response. They ask, “What is it like to teach amidst educational change?” (144). In response to this central question, Margolis and Nagel recommend that to understand effective change, policy-makers and administrators in particular should conduct “inquiry into teacher meaning-making” (146). It would make sense, then, to gather data for decision-making that take seriously the lived experience of the classroom, for we teachers are the ones, more than any other “stakeholders,” who will have to live with it.

When it comes to the design and structure of basic writing programs, faculty members have a strong interest in designing and conducting a meaningful assessment process—after all, the results of these particular assessments may determine our basic working conditions and may or may not adequately take into account our perspectives. The mood nationally can tend towards radical change and experimentation, with state legislatures ending mandatory remediation in several states and well-funded political advocacy groups like Complete College America exerting pressure to reform. Basic writing programs at community colleges may be particularly vulnerable both to externally-imposed mandates and to stumbling along in the status quo. Often without a designated WPA at the institution and often facing an ambiguous status departmentally, basic writing faculty may find that program changes are difficult to make and that “decisions” are sometimes nothing more than unreflectively validating the status quo. How, then, to assess and innovate basic writing programs? By considering innovative program changes from a variety of angles and trying to reach a decision locally through consensus, teachers can make meaning even while embracing innovation.

At the community college where I teach basic writing and composition, Prairie State College, English faculty members tried to shape a process for innovation that would be guided primarily by what would be best for teaching and learning and secondarily by concerns about numerical representations of students’ experiences. We were concerned about students in English 099, our highest level of developmental writing and reading, which enrolled more than half the students in our basic writing program. From 1985 to 2005, Prairie State offered separate 4 credit hour courses, English 099 and Reading 099, for students whose placement tests indicated a need for more instruction in writing and reading. With support from a federal Title III grant in 2005, we combined these two courses into a single, 6 credit hour English 099 class that combined instruction in reading and writing. Often, these 6-credit hour courses were taught by two faculty members who shared responsibility for the class and designed a customized curriculum. We adopted this course structure based on a pilot study and research that suggested that learning communities boost student success in developmental courses and that literacy instruction is most successful when the skills of reading and writing are taught together and not separately. (On learning communities, see for instance Visher, Weiss, Weissman, Rudd, and Wathington; on integrated reading and writing , see for instance Shanahan, or Goen-Salter, or use the key words "integrated reading and writing" to search for programs.) Yet after an initial increase in the number of students who earned a passing grade, the levels of student success dropped and then plateaued at about 58% (meaning that about 58% of students enrolled earned an A, B, or C). Moreover, and just as important a reason to reconsider the course structure, experiences in the classroom were mixed. At least once per semester, we convened as many English 099 instructors as possible for faculty and curriculum development, and teachers reported that students tended to take the “writing” aspects of the courses more seriously than the “reading.” On the other hand, we recognized the depth of learning possible with this resource-rich, time-intensive course structure.

A subcommittee of our English Department, consisting of both full-time and part-time members, met monthly during the 2011-2012 academic year to discuss possible changes to the ways we structure the 6 credit hour, integrated English 099. In early 2010, I had met Peter Adams, then a professor at the Community College of Baltimore County (CCBC), through a faculty development grant project with which we were both involved, Global Skills for College Completion (funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation). I heard from Peter firsthand how the “Accelerated Learning Program” (ALP) at CCBC was structured and, like so many others in our field, immediately wondered how we could try something like this on my campus. Others in our department were open to experimenting, too; many recognized that we could probably design a better way to teach our students than what we currently had in place, even if it meant giving up some of what a class can accomplish when it meets for 6 hours every week.

We considered some other popular models, such as a “Stretch” or “Studio” model (see Lalicker), but as the majority of our funding is tied to credit hours, we needed a structure that would involve enrolling students in a course.

Once we decided that we wanted to try piloting an ALP-style version of English 099, we then met with our administration, where we encountered surprising resistance, not to the idea of acceleration or even experimentation, but, it seemed, to the idea of writing instruction itself. (The nature of that administrative resistance could be the basis for its own article.) Ultimately, our administrators wanted to test their own assumptions about what would help basic writing students: fewer credit hours and fewer students in a learning community combination with a general education class. While this wasn’t our original idea, it seemed worth trying, especially since offering a general education learning community option seemed like the only way to get our administrators to try out an acceleration model.

We decided to experiment for two years, running some sections of the course as 6 credit hours and others as 3 credit hours. Many of the 3 credit hour sections were run ALP-style, limited to 8 students and linked with a section of English 101, the general education course students need to earn an associate’s degree or many of our certificates. In the first year, all ALP-style English 099s were taught by the same person teaching English 101; in later years a few sections have been taught by different faculty members. Following our administration’s plan, other 3 credit hour sections of English 099 were linked, as learning communities, with general education courses in other disciplines. We would have, then, four different versions of the course running at the same time—an ungainly way to run a pilot, but, under the circumstances, probably the only way we would be able to experiment with the structure of the course.

But with both a 6 and a 3 credit hour version, how would our college’s advisors know which section students needed to sign up for? Again, we reached a compromise. Initially, we wanted any student who would have tested into English 099 to be able to select which section to take, but our advisors were nervous that students would find it difficult to accept having to take a 6 credit hour section just because the 3 credit hour sections were full. Advisors and advising structures play a critical role in helping students begin their college experience (see, for instance, Persons, Rosenbaum, and Deil-Amen, comparing the student services at two-year for-profit and community colleges), and it seemed wise for us to listen to our colleagues’ concerns, especially since advisors (not the teachers) would be the first to have to explain policies to potentially upset students. The fairest solution seemed to be based on an imperfect but ostensibly objective measure: we would revive the COMPASS Reading score we had used for Reading 099, so that a student with a COMPASS Reading score of below 75 and a writing placement essay that indicated a need for basic writing instruction would take the 6 credit hour version, while a student who scored above 75 on the COMPASS Reading exam and whose writing placement essay indicated a need for basic writing instruction would take a 3 credit hour version. The four versions, then, would look like this:

1. 6 credit hour English 099, integrated reading and writing instruction, not linked to English 101, sections of 24 students

2. 3 credit hour English 099, writing instruction only, not linked to English 101, sections of 24 students

3. 3 credit hour ALP-style English 099, writing instruction only, linked with English 101, usually taught by the same instructor, sections of 8 students

4. 3 credit hour learning community-style English 099, writing instruction only, linked with a general education course, sections of 18 students

During this two-year experiment, we would examine each configuration intently and from different angles. Foremost in our discussions were our classroom experiences and our knowledge of students as learners, but we also examined numbers on student success and persistence, conducted focus groups with current English 099 students, talked with colleagues in other departments at the college who interact with and support our students, and conducted classroom observations.

At the end of the experiment period, we decided that we should turn all sections of English 099 into a 3 credit hour course that would incorporate instruction in reading and writing. And, still following the ALP model, some sections would be paired with English 101 and others would stand alone. Instead of 8 students, we would enroll 10; attrition had led to some very small class sizes in some sections, and we didn’t have enough English 101 sections to guarantee an “accelerated” seat for each English 099 student. We would also change the way we talked about the course with students, framing the basic writing course more strongly as a stepping-stone to their transfer composition course. Students could choose between two paths, either a two-semester sequence starting with English 099 and then moving to English 101, or a single semester of English 099 and English 101 taken together. In both cases, the “choice” involves completing English 101—rather than focusing on which version of English 099 to complete, we hope that students will see English 099 not just as some arbitrary requirement, but in its proper context as something that helps them do well in the transfer composition course. The data we gathered in our assessment of these courses illustrates what a teacher-driven assessment process can look like.

The Teaching Experience

We began by talking to teachers. Faculty members’ perspectives on the 6 credit hour English 099 were mixed. Almost everyone appreciated having six hours per week to work with students, and many integrated their curriculum so that students engaged with complex readings and challenging writing assignments in dialogue with the readings. Because of the rigor of a typical departmental final exam (an assessment tool used from 2009 to 2015), English 099 students were engaging in far more complex meaning-making than they had been several years before. A typical exit exam used previous to 2009 consisted of reading and discussing a short news or opinion article and then writing a personal essay on a topic related to the article, while a typical departmental final exam (which was used from 2009 to 2015) asked students to think critically about a challenging course reading and to make connections among the course materials. This increased rigor in the assessment mirrored the kind of in-depth, intellectually challenging discussions that are possible in a 6 credit hour course; since faculty members had some freedom in selecting course readings, there was often a spirit of collaborative inquiry with students. To support and develop a rich curriculum, it is hard to top having six clock hours per week in a community of readers and writers.

Back in 2004, as we deliberated about which path English 099 should take, some teachers thought that 6 credit hours might be too many—that, in spite of the advantages of having so many hours per week, 6 credit hours might be daunting to students and that students might find it hard to muster the motivation to persist. This may have been true of our course; even under the best conditions, 6 hours per week can be a lot of time to spend with a group of people. And given the increased workload for students, falling behind even for a week can make catching up feel like an impossible task. In the ten years in which we taught English 099 as a 6 credit hour course, these remained ongoing concerns for teachers, many of whom saw their task as about motivating students as much as developing students’ literacy.

Faculty members’ experiences with the 3 credit hour English 099 were also mixed. Judging from anecdotes, pass rates, and students’ and teachers’ reluctance to sign up, the learning communities approach, pairing English 099 with a general education course, was not successful. In theory these general education learning communities are a good idea, and they seem to work at other colleges, but not so much for us. Despite marketing campaigns on campus, these learning communities were among the last sections of English 099 to fill during registration; teachers’ experiences in the classroom were negative, on balance, and led to decisions not to teach another learning community like this one; and the pass rates were below other 3 credit hour versions, the standalone 3 credit hour course and the accelerated model. The standalone 3 hour English 099s were more successful, in terms of both pass rates and teachers’ and students’ interest.

The best approach for the 3 hour English 099, and the one we decided to expand, seemed to be an “accelerated” version in which students take both English 099 and English 101. In our model, adapted from CCBC’s ALP, 8 out of 24 English 101 students were concurrently enrolled in English 099 (as noted above, we later increased this number to 10 students). Both courses were taught by the same instructor in nineteen of the twenty-one sections of our pilot project. While our experience with acceleration at Prairie State was not unambiguous, it did seem the best of the available options.

From the first semester of our experiment with acceleration, starting in Fall 2012, all ALP teachers met monthly to compare notes, share successes, and analyze failures. Whenever asked, teachers reported thinking that we should continue to offer accelerated sections, in spite of some persistent questions about how exactly the two courses should relate. The small class size can be a teacher’s dream, allowing for frequent one-on-one instruction and relationship-building with students. We tried a variety of approaches to combining the instruction—using the 099 section for more discussion of 101 readings, discussion of specially-assigned 099 readings, re-examination of concepts covered during 101, intensive peer review, extra grammar instruction, intensive practice writing timed essays, writers’ workshops, examination of rhetorical principles, supported development of 101 writing assignments, one-on-one conferencing, and more. In part this diversity reflects our department’s commitment to experimentation and pluralism; in part it reflects a mad scramble to see what would work best. While we anticipate that our teaching may yet cohere around a set of “best practices,” we know that, in every case, having fewer people in the room means that each student gets more attention. Our methods have and will continue to develop around that central fact.

The persistent complaint from our teachers in this co-requisite setting is that students tend to blow off homework assigned especially for 099. Teachers have noted this pattern with every type of assignment we have tried. Students often take English 101 seriously and will complete assignments for that class, and they will come to 099 if they have attended 101 the same day, but they will frequently not do the homework for 099. Teachers find this choice frustrating, but, remarkably, teachers who experience this recalcitrance in students still think that the accelerated 099 is a good idea and should continue.

Teachers’ experience and wisdom was the most important factor driving our decision-making. But we knew that, if we wanted to verify the viability of this new model and get the support of our administration, we would do well to consider the numbers: would the numbers show that a 3 credit hour co-requisite model was a good idea?

The Numbers

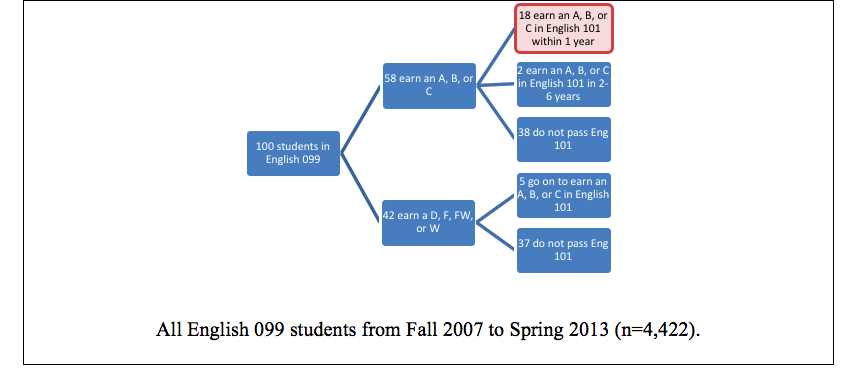

From about 2008 to 2012, when every student took a 6 credit hour course of integrated reading and writing instruction, pass rates in English 099 remained relatively stable. About 58% of students earned an A, B, or C. Yet 58% means that fewer than two in three students passed the class.

The numbers grew more dismal when we looked at these students’ records in English 101. Only about 31% of students who pass English 099 passed English 101 within one year—this means that fewer than one in five students who started in English 099 would pass English 101 within one year. Of the remaining students who passed 099, only another 2% went on to pass English 101 within six years. Altogether, about 75% of the students who began English 099 never passed English 101.

All English 099 students from Fall 2007 to Spring 2013 (n=4,422).

Our basic writing faculty members found these numbers particularly sad, as we saw the potential and dreams of so many students disappearing from our college and, presumably, higher education. While we knew from talking to students that the curriculum and course structure are only two factosr in the extremely complicated, often stressful lives our students lead, we still wondered if our curriculum and course structures could be more conducive to students’ success.

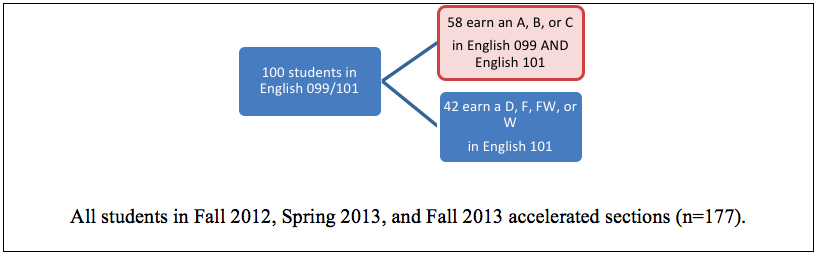

Acceleration offered some hope. In the first three semesters of our pilot project, pass rates in the accelerated sections were not significantly higher than in traditional sections. More meaningful—and statistically significant—is the comparison between how quickly students pass English 101 in each scenario. About 58% of the students in accelerated 099 pass English 101 in the first semester they take English 099.

All students in Fall 2012, Spring 2013, and Fall 2013 accelerated sections (n=177).

Based on this initial comparison and longitudinal study, the advantages seemed clear. By placing more students directly in English 101 and giving them the support they need, students actually succeeded in far higher numbers than in our previous models. Going forward, we would also need to know more about students’ success and persistence in other courses, but for now our teacher wisdom and the numbers both seemed to indicate that a 3 credit hour co-requisite model that links 099 with English 101 would be good to pursue. What did the students think about the various models we were trying?

Student Feedback

Several basic writing teachers and some advisors conducted student focus groups at the end of the Spring 2014 semester in 12 sections of English 099. No instructor surveyed her own class. Surveyors visited the classes in pairs, with one person recording students’ responses on the board and another facilitating students’ feedback. We asked four questions: What has been best about English 099 this semester? What has been least helpful about English 099? What advice would you give the English Department at Prairie State? What advice would you give future 099 students?

The raw results can be found below in an appendix. We would not want to rely on this student feedback in isolation—the focus groups were conducted in the last weeks of classes, after many students had stopped coming to class, and our students tend to be generous about the quality of their instruction. Still, it was very clear that students value small class size and the one-on-one instruction that it affords, and that they would prefer to take English 099 and 101 together in the same semester. Students’ appreciation for one-on-one instruction showed up in every version of English 099, though it was especially strong in the accelerated sections.

As a follow-up question in one section, a surveyor asked the students if they valued one-on-one instruction, why not just go to the college’s Writing Center in lieu of taking English 099? After all, the appointments are free and the consultants there are Prairie State English faculty especially trained to work one-on-one with students. The students responded that being signed up for class keeps them accountable—they said they would not have gone as regularly to the Writing Center as they went to class.

Teacher-wisdom, initial quantitative analysis, and student feedback all seemed to indicate that acceleration was the best option. We wanted to confirm that decision and gather additional qualitative data through classroom observation as well.

Teaching and Learning

I observed a single class meeting of four sections of the accelerated English 099 in Spring 2014. (I asked instructors if they would allow me to observe a representative class meeting as part of our information-gathering for the pilot program.) At their best, these sections were rigorous but relaxed, with fairly sophisticated discussions of readings and of rhetoric—opportunities for students to begin to think rhetorically as writers and as readers.

Instructors capitalized on the small class size in various ways. In two sections, students discussed a reading and a writing assignment based on the reading; they were testing ways to analyze and present concepts from the reading in their own writing. They sat together around a single large table, often with the instructor seated at the table with them, and students looked at each other as they talked, often responding to one another directly and without intervention from the instructor. Their comments tended to be on topic and it seemed to me that they were genuinely helping one another develop more sophisticated ways of talking about reading and writing. The small number of students and the classroom setup led to a seminar feeling, with few students who looked like they were suffering silently through class or hiding behind the participation of more vocal classmates.

In another section held in the same room with a large table, students composed and read their own personal writing. They sometimes responded to one another, but eventually the instructor came to dominate the questioning. Even so, each student had an opportunity to participate and receive feedback on her efforts, and the classroom atmosphere appeared to be “safe” and friendly.

At the other end of the spectrum, in one accelerated section I observed the instructor lectured about grammar for nearly the entire class period, to about 8 students. Students seemed involved and to appreciate what Rebecca Cox, citing a phrase from one of her community college student interviewees, calls “informative information”—they took notes, several asked questions, and near the end of class almost each student participated in an exercise at the classroom whiteboard (70). Later, during the focus groups, students from this section expressed appreciation for this intensive grammar instruction; several felt more confident about their ability to detect and diagnose sentence-level errors.

This wide variety could be seen as a good thing—when teachers feel empowered to experiment and share the results of their experimentation, everyone’s knowledge grows—or a bad thing, if one is convinced that some methods of instruction are ineffective or counter-productive. Over the past decade especially, our department discovered that a “live and let live,” pluralistic and experimental approach to curriculum, coupled with regular opportunities to discuss our approaches, would probably help us work together more happily in the long run as colleagues. Given our general and tacit commitment to pluralism, an open-ended and multi-faceted research process, like the one I have outlined here, offers a way to support those values while also seeking innovation and change. If we would change how we offer basic writing courses, it was important that we do so in a way that offered flexibility to experiment with instruction, and thus, discovering the wide variety of instruction already in play confirmed that the proposed changes fit with our culture and values.

Conclusions about Curriculum

In the first semester of our acceleration pilot, in Fall 2012, we tried a number of approaches and met to compare notes. At that point, most instructors began to realize that this co-requisite version of 099 worked best when it explicitly supported English 101; as noted above, when instructors treated it as a separate class, with additional reading and writing assignments that are not directly tied to helping with 101 papers, students frequently refused to complete the 099 work. Yet the time in 099 could be well spent by focusing more closely on the 101 readings or discussing related readings that were optional for the 101 students; planning, writing, revising, or peer-reviewing 101 essays and assignments; and continuing the instruction from 101 by following up with students’ questions and more practice.

As we move forward, we continue to encourage experimentation with English 099 instruction, though we encourage all instructors to aim for the following:

1. Teach in a way that makes the most of a small class size;

2. Make explicit the connections between 099 and 101;

3. Support students' reading through attention to the reading process and their own tendencies as readers; and

4. Support students’ writing through attention to the writing process and their own tendencies as writers.

In sum, we believe that our accelerated English 099 has the potential to support students as they begin to think like college readers and writers.

A Better Decision-Making Process

We found that the integrity of our decision-making process gave us confidence in our choice, provided a wealth of information about what it’s like to be in those classes as students and as teachers, and informed our ongoing discussion about curriculum development and course goals. By analyzing information obtained from teacher focus groups, quantitative results, student feedback, and classroom observations, rather than simply adopting a model that seemed to have worked for other colleges, we have a stronger sense of the advantages and disadvantages of our choices. We would have had an even better understanding if we had also systematically collected and analyzed representative student work from various sections. We did, however, discuss what we had learned from several recent years of end-of-semester faculty meetings in which teachers presented a few examples of passing, borderline, and failing work from students in each section. Going forward we hope to analyze student work more systematically as a part of how we evaluate our acceleration program.

We see great wisdom in asserting local control as teachers, even if we are responding to national concerns, and in making the lived classroom experience the main factor in colleges’ decision-making

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Prairie State College English Department, whose commitment to our students and lively interest in teaching has challenged and shaped me over the years. I would also like to thank Thomas Nicholas for his help in verifying the accuracy of the numbers here.

Appendix: Small Group Instructional Feedback from 3 of the 4 versions of our pilot project

6-hour English 099 integrated reading and writing classes

Students in these classes seemed to enjoy their instructors and to enjoy the kinds of readings they were asked to do (usually challenging texts, often trade paperbacks). Some sections had a single instructor for all 6 credit hours, while other sections had two instructors who divided the time. As a follow-up to the third question, about advice to our department, we asked whether they’d rather have a single, 6-hour class that combined reading and writing or two, 3-hour classes that each had a separate focus. Students almost unanimously seemed to prefer the single, 6-hour class. The responses below are grouped according to general theme.

What has been best in English 099 this semester?

Teacher/pedagogy

1. caring and joyful instructor who is understanding about problems and is flexible

2. teachers will work with you

3. teachers’ interaction with students

4. group activities

5. peer review

6. individual conferences

7. extremely detailed and organized syllabus helps students keep on track and know what’s coming

8. professor meets students where they are in terms of skills/knowledge (taught at right level)

9. professor emails class the homework right after class

Curriculum/program

1. interesting readings (this came up three times)

2. don’t have a textbook

3. English + reading together

4. many assignments completed during class--helps not only with feedback but with time management

5. meeting in a computer lab helped students get immediate feedback from professor as they worked on their writing

6. refresher out of high school

7. grammar

What has been least helpful about English 099?

1. more time in a computer lab would be helpful

2. the old peer review (which the instructor stopped doing)

3. confusing having two teachers (in a team-taught section)

4. Pearson MyWriting Lab (used in only two sections) - overwhelming, covers too much; students would like to see certain areas prioritized over others, and perhaps better preparation before taking diagnostic test; concern that diagnostic assesses how well students take tests

5. some students in a class that met in a computer lab voiced a desire to interact more with peers

6. use Desire2Learn (our Learning Management System)

7. let students know about progress/status in the class

8. mad that class doesn’t count for grade (these developmental courses are not credit-bearing and do not factor into students’ academic grade point averages, though students do receive letter grades which factor into financial aid grade point averages)

9. final exam is too much a part of the final grade

Advice to PSC English Department (not all focus groups had time for this question):

1. would have liked taking 099 + 101 together, though some students expressed reservations about the workload

2. in one section, all students preferred a combined reading and writing class—they predicted that separate classes would feel like more work; concerned about having two separate syllabuses, more to keep track of, etc.

3. in another section, overwhelming support for a combined reading and writing class, citing close ties between the disciplines.

Advice for future English 099 students:

1. come to class (this came up three times)

2. do homework

3. be eager to learn

4. use Desire2Learn, keep up

5. get and keep study skills packet

6. don’t fall behind (this came up twice)

7. work ass off

8. be sure to get help

9. 4 days/week - hard to work around

10. confusing having different teachers

11. like coming every day

12. 3 hours is too long for one class period

13. need more time on final

14. save everything! Never throw anything away

15. don’t be ashamed of being placed into English 099; this placement discourages some students but they should see it as an experience and opportunity

16. ask questions

17. take notes

18. be on time

19. don’t leave early

20. make sure you’re in the right spot

3-hour ALP-style classes

These students were glad to have taken the two courses together (though it should be noted that in many cases the class size was small at the end of the semester). They appreciated the small class size and the chance to follow up on work from English 101. It seemed that students felt they learned well from hands-on class activities, such as revising and writing, with a chance for immediate feedback from the instructor.

What has been best about English 099 this semester?

Teacher/pedagogy

1. connection to students

2. one on one focus in 099

3. ask questions in 099

4. wonderful teachers/peers

5. more feedback, more perspectives (in a team-taught 099/101 combo)

6. one-on-one support

7. personal help

Curriculum/program

1. apply what you’re learning – i.e. grammar

2. extra help/more organized for English 101 - didn’t feel so alone

3. helped with English 101

4. small class size

5. this class would benefit everyone

6. grammar instruction supports 101

7. stepping stone for 101

8. simultaneous instruction is relevant rather than 099 in one semester and 101 the next semester

9. review of sentence structure

10. support with learning punctuation rules

11. identifying sentence errors/run-ons

12. extra support for 101

13. essays were good

14. revising/writing during class time, which gives opportunity to get immediate feedback from instructor

15. having opportunity to ask questions/better understand 101 content

16. getting additional instruction in grammar

17. reading - short fiction for 099; they were interesting and intriguing, led to good class discussion, and the summary and paraphrasing work helped for 101

18. extra practice for 101

19. nuts and bolts were in Desire2Learn

20. extra time with 101 readings

21. working with a topic

22. small group/asking questions and talking

What has been least helpful about English 099?

1. more feedback, more perspectives (in a team-taught 099/101 combo)

2. explain consequences more clearly during advising/registration

3. the essays were overkill

4. need for more clear/varied explanations of material ~ don’t want to be told “you should already know this”

5. lack of feedback/grades on homework assignments, general uncertainty about grade in class

6. in one section, three out of five students strongly felt that the 099 class should meet PRIOR to the 101, as to prepare them for the upcoming 101 session (where they sometimes felt lost/overwhelmed); the other two argued that they could see advantages to meeting afterwards

7. summarizing & paraphrasing stories - liked this part of 099 the least

8. so much writing

9. need more in-class assignments, not just in Desire2Learn

10. waste of time/forced to take this class

11. shorter time--40 min?

12. Intentional Advising seems like a sales pitch (our Student Affairs division assigned an advisor to each section; students were encouraged to meet with advisors outside of class and advisors also made several presentations in class throughout the semester)

13. 3 credits but could be fewer

14. needs more focus on writing & grammar

15. need more writing practice

Advice to PSC English Department (not all sections had time for this question):

1. find a balance in the 099 essays and assignments (i.e. quick writes and in-class writing is good)

2. more assignments to offer technology support

3. being signed up for class keeps students accountable (rather than suggesting going to the Writing Center)

4. do it again this way

5. it’s like an extra perk, taking 099

6. in old 099 version, students get discouraged—in this one, students are encouraged

7. liked having same teacher

8. only learning community I’ve liked (from a student who took a Biology/English learning community)

Advice for future English 099 students:

1. go to both classes

2. be on time

3. bring 101 stuff to 099

4. go to Writing Center

5. use the 2 heads [instructors]

6. treat as 2 different classes

7. do your homework (this came up twice)

8. come every day (this came up twice)

9. be open to 101 concepts and methods

10. be prepared to refer to your notes

11. be prepared to write

12. learn from/cooperate with fellow students

13. stay on top of things

14. don’t wait until last minute

15. if you don’t get it in 101, ask in 099

16. go to Writing Center (make it mandatory?)

17. write a better essay so don’t have to take 099

18. have teachers focus more on topics in 101

19. Eng 099—reading books; don’t see connection

3-hour non-accelerated/stand alone version

These students noted that one-on-one time with instructor was helpful and most would have preferred to take English 099 and English 101 together at the same time (see comments to English Department).

What’s best about English 099 this semester?

Teacher/pedagogy

1. open class discussions; our opinion matters

2. one-on-one time with instructor

Curriculum/program

1. Learning to organize essays

2. how to plan for essay writing

3. needed review of English concepts

4. textbook writing assignments due each class period

5. discussion of homework

What was least helpful about English 099?

1. being stagnant after the review has served its purpose

2. learn more from class than doing homework

Advice to PSC English Department:

1. I would rather complete 099/101 to expedite my graduation; also, I won’t forget what I learned in 099

2. I would like to get one-on-one help in the 099/101 linked

3. 099 should support 101 as a low-key type of tutoring

4. make book available before class

Advice to future English 099 students:

1. read the book ahead of time

2. don’t take class for granted

3. we need support of 099 to succeed in 101

Works Cited

Cox, Rebecca. The College Fear Factor: How Students and Professors Misunderstand One Another. Cambridge: Harvard, 2010. Print.

Goen-Salter. "Critiquing the Need to Eliminate Remediation. Lessons from San Francisco State." Journal of Basic Writing 27.2 (2008): 81-85. Print.

Lalicker, William B. “A basic introduction to basic writing program structures: A baseline and five alternatives.” BWe: Basic Writing e-Journal 1.2 (1999): n. pag. Web. 1 September 2016.

Margolis, Jason, and Liza Nagel. “Education Reform and the Role of Administrators in Mediating Teacher Stress.” Teacher Education Quarterly 33.4 (2006): 143-159. Print.

National Council of Teachers of English. “2016 NCTE Education Policy Platform.” National Council of Teachers of English, 2016. Web. 1 September 2016.

Shanahan, Timothy. “Reading-writing relationships, thematic units, inquiry learning...in pursuit of effective integrated literacy instruction.” The Reading Teacher 51.1 (1997): 12-19. Print.

Person, Ann E., James E. Rosenbaum, and Regina Deil-Amen. “Student planning and information problems in different college structures.” Teachers College Record 108.3 (2006): 374-396. Print.

Visher, Mary, Michael J. Weiss, Evan Weissman, Timothy Rudd, and Heather Wathington. “The Effects of Learning Communities for Students in Developmental Education: A Synthesis of Findings from Six Community Colleges.” MDRC July 2012. Web. 1 September 2016.

Jason Evans

Jason Evans is Professor of Developmental Writing and English at Prairie State College in Chicago Heights, Illinois.