Learning Journals in One ALP: Making Visible Students’ Voices

About Writing Ability and the Non-Cognitive Context of Learning

Stephanie Kratz

____________________________________________________________________________________________

ABSTRACT:This article describes how an ALP writing assignment provided a forum for student-faculty dialogue about academic and non-cognitive issues; and served as both a program and student assessment tool. Qualitative and quantitative studies reveal that students often mistakenly believe they are proficient regarding grammar and success strategies alike. Faculty can support students by recognizing that student success is tightly bound to the context in which students learn, and striving to create an environment that explicitly addresses grammar and success concepts. ____________________________________________________________________________________________

Many resources are invested in the redesign of an academic program, and therefore careful curricular planning is key to success. When Heartland Community College (HCC) redesigned our developmental English program, we devoted time and resources towards the creation of a new course built to help students succeed. Specifically, we adopted the Accelerated Learning Program model from the Community College of Baltimore. In addition to new course materials, we developed feedback tools like surveys for students and faculty and data collection templates to record grades and retention. We wanted to know how well the new course performed. What we did not expect was that one of the most useful student and program assessment tools would turn out to be a set of writing assignments called Learning Journals. Written to complement the student success principles (described later in more detail), the Learning Journal assignments require students to reflect in writing about their learning and academic choices. While offering writing practice, the journals simultaneously offered faculty an opportunity to dialogue with students about their performance in class and shed light on students’ non-cognitive issues as well as writing skills. The Learning Journals helped make student voices heard, giving faculty insight into what students were thinking, learning, and experiencing. In this essay, we will describe the concepts upon which the Learning Journals are based, the qualitative and quantitative assessment data we collected, the benefits of the journals for both faculty and students, and the missed opportunities that we have learned from as our program scaled-up.

Like other colleges, HCC chose the ALP model to support students who struggled in the traditional developmental English course sequence. HCC is an open-admission community college in central Illinois with a student population of approximately 5,000 credit students. The HCC English faculty and administration moved forward with a developmental English redesign because of poor retention benchmark data and low persistence rates in our traditional program. After three years of research, collaboration, and much learning on our part, we decided to adopt the ALP model first pioneered by the Community College of Baltimore County (CCBC). We chose this model because of the benefits that it offers students as well as its demonstrated success at other community colleges.

Much has been written about the success of accelerated programs at CCBC and across the country. A Community College Research Center study of the ALP at CCBC found that “participation in ALP is associated with substantially better outcomes in terms of English 101 completion and English 102 completion” than students in the traditional developmental English course sequence (Cho et al. 23). Nationwide data from the California Acceleration Project and Achieving the Dream have shown that success rates for developmental students increase the sooner they can enroll in college-level courses: “Student completion rates in college English and Math drop with each additional level of remedial coursework required” (Hern 1). In the ALP, students accelerate through developmental English and college-level English during the same semester, cutting in half the time required to complete remedial coursework; cohorts of eleven students and one instructor spend six hours a week together; and ALP faculty consciously attend to non-cognitive issues that affect student success. The Center for Applied Research (CAR) studied the implementation of seven adapted ALPs. They concluded that all colleges in the study experienced success even when the CCBC model was modified (Coleman 33). Like the colleges in the CAR study, HCC adapted the ALP model to fit our institution. We wanted to ensure that our new course – although a support for first-year composition – also had its own identity with its own learning outcomes, grade, and expectations.

Redesign Process

The bulk of the creation of our new course – English (ENGL) 099 - occurred in conjunction with an on-campus Faculty Academy about course design based on L. Dee Fink’s Creating Significant Learning Experiences. Using Fink’s principles of a learning-centered approach to course design, taxonomy of significant learning, and Wiggins’ concepts of backwards design, we created learning outcomes (see Figure 1), learning journal assignments (Appendices A and B), rubrics, a syllabus, calendar, grading philosophy, and a course assessment plan for ENGL 099. In addition to receiving support for their concurrent ENGL 101 course, students in ENGL 099 write journals, review grammar concepts, and participate in embedded student success services like in-class visits from advisors and trips to the Writing Center.

Figure 1: ENGL 099 Learning Outcomes

|

Throughout our faculty-led redesign process, the HCC administration funded faculty attendance at conferences including the Conference on Acceleration in Developmental Education; paid faculty to research and plan the new course; dedicated time from many campus departments including Advising, Enrollment Services, Instructional Technology, Marketing, and Tutoring; and compensated ALP faculty at the same rate as any other class even though ENGL 099 is capped at 11 students. Administrative support made this redesign possible, and open communication with many departments across campus was key to maintaining the balance of reinforcing ideas across courses without being repetitive.

Perhaps the most useful resource provided by the administration was that of reassignment time for a faculty member to serve as ENGL 099 Coordinator. Our department chose a senior faculty member with over ten years of developmental teaching experience. The Coordinator assumed responsibility for many tasks that a faculty member who was teaching a full load would not have time to do. Implementation of the new course was gradual and purposeful, beginning with two sections in its first semester and only scaling-up to program-wide implementation after that. Indeed, CCBC and CCRC recommend that colleges that are adopting an ALP “start small but plan large” (McKusick et al.). The ALP grew from two sections during the pilot semester to complete scaling-up, enrolling approximately 425 students over the course of six semesters. The Coordinator managed the scaling-up process, trained all ENGL 099 faculty via workshops and a faculty handbook, facilitated communication among faculty via bi-weekly meetings and a bi-weekly newsletter, championed the course via communication with stake-holders across the college, researched how ALP has been implemented across the country, developed digital course materials, and served as the primary troubleshooter for technology-related issues.

In order to study the effectiveness of ENGL 099, the Coordinator also facilitated collection of both quantitative and qualitative data. Once the data were collected, the Coordinator:

- Analyzed 099 student Learning Journals for themes about students’ college concerns in order to inform faculty about students’ non-cognitive issues.

- Analyzed 099 Learning Journals for grammar and punctuation correctness over the course of the semester in order to assess student transfer of these concepts from in-class reviews to their own writing.

- Surveyed 099 students regarding their attitudes about writing, learning, and placement into ENGL 099 in order to assess students’ satisfaction with the redesigned course.

- Collected information about 099 students including hours worked during the semester, status as a first-generation college student, grades in high school English classes, and whether they had taken a student success course. These data helped us get to know our students.

The purpose of gathering data was to assess the redesigned course. Together, the Coordinator and the faculty made adjustments based on our findings. For instance, students’ struggle to transfer grammar and punctuation knowledge prompted faculty to experiment with various types of instruction which is described in detail later in this article. Comparing non-cognitive issues of students across all sections helped us see trends which confirmed that attention to these concerns was crucial to student success. Data collection supported our hunch that our students would benefit from many of the same services as students at CCBC.

Addressing Non-Cognitive Issues

Many developmental students enter the classroom filled with anxiety or doubt about their ability to perform well in an English class, or anger at having been placed there in the first place. These non-cognitive issues are a primary barrier to student success in basic writing and therefore in college. If we are to have any success at reaching these students, we must attend to their non-cognitive concerns. As Rebecca Cox argued in her book The College Fear Factor: How Students and Professors Misunderstand One Another, “Uncovering and understanding students’ preconceptions and expectations should take precedence in the process of rethinking learning objectives and the means of accomplishing them” (164). Getting to know students and their emotions is as important to the success of an accelerated developmental English course as the curriculum itself.

One of our adaptations of the ALP model reflected HCC’s college-wide focus on student success skills. At the same time that our developmental English program was being redesigned, HCC implemented a new requirement that all students who placed into two or more developmental courses must also enroll in General Studies (GENS) 105, a student success class. Like many colleges across the country, we were trying to increase the amount of support and reduce the number of exit points for at-risk students. We adapted Skip Downing’s On Course curriculum in both ENGL 099 and GENS 105. On course synthesizes best practices from psychology, education, business, sports, and personal effectiveness and maintains that successful students embody eight characteristics. According to the On Course principles, successful students (1) accept self-responsibility; (2) discover self-motivation; (3) master self-management; (4) employ interdependence; (5) gain self-awareness; (6) adopt life-long learning habits; (7) develop emotional intelligence; and (8) believe in themselves.

Four of the principles speak directly to the ENGL 099 learning outcomes: successful students assume personal responsibility, are adept at self-management and self-motivation, and believe in themselves (Downing). To help our ALP and student success courses to complement each other, we took the lead from Downing’s use of written journal assignments and created Learning Journals, taking care to avoid overlap between the courses.

One goal of the ENGL 099 Learning Journal assignments is to increase dialogue between students and teachers about non-academic issues that affect students’ education. Two of the features of ALP that are crucial to its success, according to the founding program at CCBC, are that “ALP instructors consciously pay attention to helping ALP students develop successful student behaviors” and “ALP instructors consciously pay attention to issues from outside the college that may have a negative impact on ALP students” (“Features”). In all, we developed ten Learning Journal assignments from which each faculty member chooses at least five to assign during the semester. (See Appendices A and B for two examples.) Learning Journal topics include the student’s preferred writing environment, challenges and opportunities faced by students during the semester, goal-setting for writing projects, reviewing those goals, self-evaluation of the student’s class participation, managing writing-related campus resources, reflection on language convention activities, explorations of the types of writing that students may do in the future, reflections on lessons learned during the semester, and letters to future students. Each assignment encourages students to view a specific skill related to college writing through the lens of student success and the ENGL 099 learning outcomes.

One Learning Journal was assigned approximately every two weeks, frontloaded to the start of the semester when improvement in students’ choices can have the biggest impact. The Learning Journals have changed from one-off, reflective pieces to multi-draft mini-essays. After students wrote a first draft, instructors provided feedback about non-cognitive issues and surface-level correctness. Students then revised and/or discussed their journal entries with their instructor. (More on the evolution of how surface-level correctness was weighted later.) Throughout all of the assignments, students were encouraged to refer to specific examples of writing projects including concurrent ENGL 101 projects. Students practiced using these specific examples as support for discussion of their choices and strategies, and instructors were able to comment on the progress of ENGL 101 projects as they happened.

One ENGL 099 learning outcome states that by the end of the semester, students will be able to “demonstrate responsibility for their own learning including attending class, completing required work, identifying what they do not know, and framing useful questions to help them move forward.” A corresponding Learning Journal assignment, Evaluate Your Participation (Appendix A), asks students to reflect on their participation in both ENGL 099 and 101 and to make a participation plan for themselves for the remainder of the semester. Rather than passively receiving evaluation, the assignment requires active engagement in self-assessment as students identify their strengths and weaknesses.

Qualitative analysis of common themes in student Learning Journals provided a forum for student-faculty dialogue. In his Evaluate Your Participation journal, one student in my class expressed concern about the nervousness he felt during class discussions. Simon wrote, “I am engaged, responsible, and respectful. The only flaw I have is I’m Very [sic] shy. When my teacher asks, ‘Does anyone have any questions?’ I ask questions, but in my notebook. Then at the end of class I ask my instructor and she informs me with the proper information.” Via written feedback to Simon, I was able to affirm his idea for the strategy of writing down questions that he is too shy to ask during class: “Being quiet is not usually a problem. You are always following along even if you are not speaking up. I suggest continuing to challenge yourself to speak up, however, as this is an important skill that you will need in life and in other classes. Using a question notebook is a great idea. Perhaps you can write out what you want to ask before you ask it aloud in class.” Simon and I had several conversations about strategies for dealing with nervousness during class. It may have been his nervousness at being judged by others that contributed to another behavior that proved problematic.

Simon had also been struggling with arriving to class on time. He was late more often than he was on time, and his arrival was often disruptive to the class. Simon made no mention of his tardiness in his Learning Journal entry, suggesting that he was unaware that this was a problem. He wrote, “Personally I feel I deserve a B [for participation]. I am attentive in class even though I stay in silence. I admire my classmates, regarding their ideas and concerns. I take charge of my assignments making sure they’re in on time. This is my job.” Simon’s understanding of the participation requirements for a B were different than my understanding of them, and I was able to address this in my comments to his journal. It presented a moment for me to comment on how his behaviors might affect his success. Similar to a FYC assignment described by Cox, the Learning Journals were “a mechanism for developing the teacher-student relationship [that was] built into the structure of the course” (Cox 128). Not only was Simon able to practice organizing and expressing ideas, the topic of the assignment revealed his assumptions about the implications of his behavior.

As students like Simon begin to see their ability to make more effective choices, they develop what Dweck calls a growth mindset. In a 2015 reflection on her book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Dweck states that student effort, while important, is not enough. Students also require feedback from people who are experienced in academia: “Certainly, effort is key for students’ achievement, but it’s not the only thing. Students need to try new strategies and seek input from others when they’re stuck. They need this repertoire of approaches—not just sheer effort—to learn and improve” (Dweck “Revisited”). As students move through the struggles of the semester, a growth mindset teaches them that they can benefit from the support of a classroom of peers and campus resources.

As students reflected on their progress or lack of it, the Learning Journal assignments challenged them to see the purpose in the 099 assignments and curriculum. In her late-semester Letter to a Future Student (Appendix B), Clary referred to her initial frustration about being placed in the course: “Dear future ENGL 099 student, I know the last thing you probably want to do is sit through lessons about proper grammar and the structure of a sentence. It can feel tedious – and if it is something you struggle to understand I know that can be beyond frustrating.” After acknowledging her initial frustration, Clary goes on to explain how not only her effort but her use of resources helped her persist.

I would also strongly advise taking advantage of the extra time you get with your teacher and any teacher’s aides available . . . considering this is a class that is taken in conjunction with English 101 and can really excel your chances to succeed with the papers you must write during that course . . . Don’t ever be afraid to use the help offered – I know it can be tough to want to admit if you’re a [sic] struggling but just remember you are not the only one.

This assignment provided an opportunity for Clary to reflect on how her non-academic struggles are not insurmountable. Specifically, opening up the conversation about such issues helps students track any changing attitudes--in this case, Clary’s realization that she can benefit from working with others even though it requires a time investment.

Developmental English students at a community college often balance school, work, and family responsibilities. At HCC, over fifty percent of ENGL 099 students work twenty or more hours per week. They are easily distracted from success in class if their lives get off-balance, but support and encouragement from developmental English teachers can help them succeed. Specifically, advice about how to navigate the college landscape—which can be overwhelming even for college-level students – can help students become members of the academic community. In its “White Paper on Developmental Education Reforms,” the Two-Year College English Association recommends that faculty, administrators, and legislators “fund and develop strong academic support systems for students” (228). How better to provide support than to simultaneously offer campus resources and complement that with assessment tools that are built into the curriculum? Although the Learning Journal assignments aren’t the only way to address these non-cognitive issues, they have provided us one way to accomplish Cox’s suggestion that we uncover and understand students’ preconceptions and expectations.

Transfer of Language Conventions

The Learning Journals provided information not only about students’ non-cognitive needs but also their writing skills, specifically grammar and punctuation or what HCC’s Writing Program calls “language conventions.” Instruction about sentence-level grammar and punctuation concepts is an issue that we have wrestled with since before the creation of ENGL 099. When students arrive at our open-admissions college lacking proficiency in the concepts taught to them in elementary and secondary school, a difficult issue arises for English faculty: how best to teach grammar to students who have already failed to learn it in traditional ways. As we collected ENGL 099 student writing samples, we continued to wrestle with the issue of how best to teach grammar.

One ENGL 099 learning outcome states that by the end of the course, students will be able to “identify strengths and weaknesses in their understanding of language conventions including grammar, spelling, punctuation, and MLA documentation and formatting.” Over six semesters, in spite of all our efforts to best serve students in terms of grammar instruction, we kept facing the same result: students’ inability to transfer their knowledge about language conventions to their own writing. Perkins describes transfer of learning as “how knowledge and skill acquired in one context for one purpose impacts performance in other contexts for other purposes” (38). It’s one thing for students to understand the rules and quite another for them to apply those rules.

Seeking the most effective approach to teaching language conventions, the faculty experimented with three different instructional approaches to teaching grammar over six semesters:

- One approach was for students to complete the comprehensive diagnostic test of an online software program produced by an educational publishing company. The program then created an individualized plan of study for each student.

- A second approach was for teachers to diagnose students’ needs via their own writing and then assign individual topics in the online program.

- A third approach was similar to the second, but instead of assigning tutorials from the online program, students were directed to consult instructor-provided grammar and punctuation resources, many of which were free online.

Throughout our experiment with the three approaches to teaching language conventions, we continued to see the same common errors: unnecessary commas (“The easiest writing task that we did I thought was when we had to revise our writing pieces because, it was already written we just had to reread it and make it better”), incorrect usage (“It can help you become a better writer if your writing is not very well”), and comma splices (“[The essay] was so confusing to me and I didn’t really know what to do, I had to find the history . . .and talk about it”). Why, we wondered, were students demonstrating an understanding of language conventions rules during class activities but still struggling to apply those concepts to their written work?

We turned to the students’ writing to search for answers. Forty student Learning Journals—one early-semester and one late-semester journal for each of twenty students—were analyzed for improvement in accuracy of language conventions over the semester. Participants were chosen at random from semesters associated with each of three instructional methods. Following the research methods of Connors and Lunsford, improvement was identified based on a count of errors. Connors and Lunsford cite three studies from three different years (Johnson in 1917; Witty and Green in 1930; and Connors and Lunsford in 1988) which demonstrated that surface-level errors were not a trend. In fact, the number of errors over the years was remarkably similar: between 2.11-2.26 errors per 100 words (Connors and Lunsford 406). Admittedly, this type of research has limitations. For instance, English teachers and linguists sometimes disagree on the rules of correctness.

Consider, for example, the Oxford comma or the singular use of “they.” Connors and Lunsford acknowledge that "teachers' ideas about what constitutes a serious, markable error vary widely" (402). In spite of the differences in marking rules, however, both the early - and late-semester ENGL 099 Learning Journals were marked by the same researcher to determine changes in error over the semester rather than total number of errors in the sample.

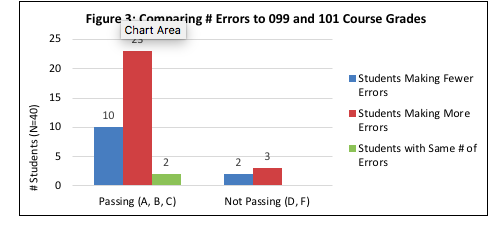

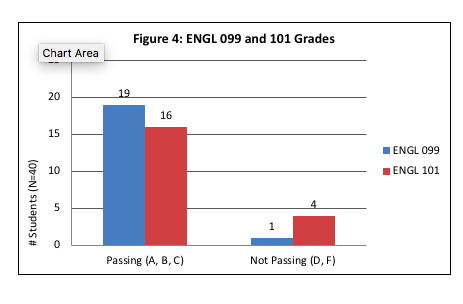

The results of the current study found that although students made more errors in late-semester Learning Journals than early-semester, the percentage of errors per 100 words decreased. (See Figure 2.) In fact, of the 35 students who passed both ENGL 099 and 101, only ten of them actually made fewer errors in their writing. One made the same number of errors, and twenty-three made more errors. (See Figure 3.) One more piece of data further muddled the picture: Although the number of errors increased, success rates in both ENGL 099 and 101 were high (See Figure 4.) Additionally, neither the accuracy of students’ language conventions nor the instructional method was connected to passing grades in ENGL 101. Regardless of instructional method, eighty percent of the students in the sample passed ENGL 101 with grades of A, B, or C. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 2: Errors Per 100 Words in Early- and Late-Semester Learning Journals |

||||

Learning Journal |

Sample Size |

Average LJ Length |

Average Errors Per LJ |

Errors Per 100 Words |

Early-Semester |

20 |

346 |

14.4 |

4.17 |

Late-Semester |

20 |

538 |

18.5 |

3.44 |

Figure 5: ENGL 101 Grades by Instructional Method |

||||||||

|

Instructional Method |

|

||||||

Grades |

A |

B |

C |

Total |

||||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

Passing (A, B, C) |

6 |

85.7% |

4 |

66.7% |

6 |

85.7% |

16 |

80.0% |

Not Passing (D, F) |

1 |

14.3% |

2 |

33.3% |

1 |

14.3% |

4 |

20.0% |

How to make sense of all the statistics? Although the ALP did not “cure” students’ surface-level language convention problems, it did help students succeed in a college-level course. Students still struggled with writing, but they had learned to use their resources and pass ENGL 101. The possibility does exist that students were more confused about language conventions at the end of the semester than at the beginning, but several factors seem to point to a different interpretation of the data. Some faculty observed students taking less care with the late-semester journals and speculated that the many errors were a result of a lack of proofreading. Indeed, proofreading errors (which included spelling errors) made up the highest percentage of errors in the samples (See Figure 6.). Perhaps students were focusing their efforts on ENGL 101 rather than ENGL 099 by the end of the semester. The purpose of ENGL 099 is, after all, to help students succeed in ENGL101. Perhaps the students were taking more risks in their writing by the end of the semester, experimenting with more mature sentence structure. Certainly students were producing longer texts of higher word counts which provided more opportunities for an increased number of errors. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 6: Most Common Language Convention Errors |

||

Error Type |

Number |

Percentage |

Proofreading |

246 |

37% |

Commas |

212 |

32% |

Sentence Structure |

120 |

18% |

Verb Tense |

46 |

7% |

Miscellaneous Punctuation |

27 |

4% |

Pronoun Usage |

13 |

2% |

Total: |

664 |

100% |

Implications

A careful examination of students’ ENGL 099 Learning Journals shows that the most significant information is not in the nuts-and-bolts of grammar but in the context of student learning. Consider the concept of learning transfer. Research about transfer distinguishes between the similarity of situations, or what Perkins and Salomon call near and far transfer.

Near transfer refers to transfer between very similar contexts, as for instance when students taking an exam face a mix of problems of the same kinds that they have practiced separately in their homework . . . Far transfer refers to transfer between contexts that, on appearance, seem remote and alien to one another. For instance, a chess player might apply basic strategic principles such as “take control of the center” to investment practices, politics, or military campaigns. (Perkins and Salomon 4)

For composition faculty, instruction in language conventions may seem like near transfer. But for developmental students who are struggling to juggle not only the concrete skills of language conventions but also abstract concepts like organization and rhetorical savvy in effectively addressing an audience, such skills can seem much farther apart. Add to that the non-cognitive issues of developmental students and the increased number of their surface-level errors pales in importance to their overall learning about how to succeed in college.

In writing, maintaining control of all the moving pieces of a paper is challenging, and the proofreading of language conventions can be one piece that students neglect. Students’ writing abilities are influenced by the non-cognitive context. Consider one student’s late-semester journal statement that has several language convention errors:

There are a lot of learning tasks that I caught onto quickly and some that weren't so easy for me. Things like I was very successful with were things like paragraph structure and papers as a whole. Things that were difficult for me were things like grammar and making my sentences flow . . . One thing I would of wanted to know on the first day of class would be how much work you have to put into the papers because they are not easily graded by any means. Also how much the little assignments we have matter a lot and they really do add up.

One last thing I would have liked to know would be how important is it to just listen in class and pay attention to everyone around me and what they were saying because it honestly helped a lot. (Isabelle)

Isabelle describes her strengths, weaknesses, and her learning as a whole: “As a learner I have learned that it takes a lot of work to make your papers as good as you would like them to be. I have also learned that you have to have other people looking at your papers and giving you a lot of feedback to make it better.” Isabelle’s writing shows errors in language conventions, but it also shows a mature student who is primed to succeed in ENGL 102. Those strengths, although less tangible than attention to error-free prose, are valuable in their own way.

Certainly the small sample size of this study also influenced the statistical results, and further research about the application of language conventions is needed. But the Learning Journals provided us with other types of useful information. Maybe we were depending on the journals to reflect language conventions knowledge rather than using them to reveal students’ attitudes about how best to use their resources. Was the purpose of the Learning Journals to reflect on student success choices or to reveal students’ abilities to write academically-correct sentences?

The Learning Journal assignments provided faculty members the opportunity to discuss both students’ grammar abilities and the effectiveness of their student choices. In hindsight, the qualitative and quantitative analysis of student writing samples revealed that as we adapted our curriculum to try to respond to what we perceived to be surface-level needs, we down-played the social and rhetorical contexts of students’ learning. Indeed, this tacit knowledge can be applied to both language conventions and non-cognitive issues that are ubiquitous for college students and can actually sabotage learning if they are not explicitly addressed. Struggling students may wonder at teachers’ expectations that they understand concepts about which there is little direct instruction; both grammar and student success often fit this description. Additionally, “sometimes students think that they have learned a concept when they have not” (Orsini-Jones 220). Succeeding in challenging college courses is more complicated than knowing where the tutoring center is located, and applying language conventions is more complicated than learning the rules of when to use commas.

Many developmental students lack confidence in their writing abilities. As we have seen with non-cognitive issues described by students in their Learning Journals, students’ preconceived notions and expectations affect their ability to succeed in college. Rather than challenging themselves to learn the big-picture concept, students often fall back on "rote memory and routine procedures as a way of coping" (Perkins 36-37). When an overwhelming concept like writing becomes even more complicated with the addition of required proofreading, students can lose track of their knowledge of language conventions. In twenty Learning Journals about lessons learned and advice to future students, only seven students mentioned grammar. Instead, most of the comments were about increased awareness of student success behaviors and moving beyond feelings of inadequacy as a writer or a college student. Although developmental students struggle to apply language conventions concepts, that is not evidence of a failure of an ALP. Successful students may still struggle to apply strict rules of academic prose, but their awareness of both the rules and campus resources more effectively equips them to face the real-life challenges of community college students. The question remains why students are often unable to make connections between writing skills learned in class and their written work, and the answer, I think, is that students are not able to learn effectively when they are anxious about being perceived as stupid or worried about getting to class on time after dropping their kids off at daycare.

The Learning Journals made visible students’ voices about grammar as much as their voices about affect. At HCC, we experienced the wisdom of another recommendation from the “TYCA White Paper on Developmental Education Reform”: “use multiple pieces of evidence, including student writing, to assess student needs and abilities” (228). Developmental English redesign is complex and, in its early stages, requires continuous assessment and revision. For us at HCC, although the ALP has helped us meet our goals of increased student success and reduced withdrawals, the new course looks different than many would have predicted. A singular curriculum ingredient has been helpful in many ways. The Learning Journals provided multiple opportunities for student-faculty dialogue. They opened conversations about questions related to grammar and punctuation. And they offered course assessment information by providing qualitative data to complement the quantitative data.

As ALPs scale up and evolve beyond the pilot phase, a dedication to student-faculty dialogue will keep learning alive for all. Continuous assessment and revision benefit both students and faculty.

Appendix A

Learning Journal: Evaluate Your Participation

Assignment: For this Learning Journal entry, propose what grade you deserve for class participation so far this semester. Explain the rationale for your proposed grade with evidence from the classroom. Give specific examples of ways that you have participated – or not participated. Then, write a “participation plan” for the rest of the semester. Describe what behaviors you will continue and/or what you might change. Finally, explain the reasons behind your participation plan. Why will it benefit you – and maybe even others?

Context: A portion of your course grade comes from in-class participation. For this journal, consider how you contribute to class. How do you participate? Is your participation helpful to your classmates? Does it distract others from their work? Does participation help you get the most out of class?

There are many sets of standards that teachers use to evaluate student participation. Here is one set. Your teacher may be using a slightly different set of expectations. This one is here to help jump-start your thinking.

A: Full participation by consistently asking quality questions, providing well-developed responses, and sharing knowledge with others. Demonstrates “big picture thinking” tying course concepts to class, experiences, and daily work.

B: Above average participation: student has occasional involvement in sharing knowledge. Sometimes questions and responses provided. Always respectful of others’ ideas and concerns. Not always able to connect activities with the course concepts.

C: Does what is expected: comes to class and completes assignments. Often does not engage or answer questions. Sometimes distracted and does not focus on the “big picture” concepts of class.

D: Does not demonstrate a time commitment to the course (does not attend consistently). Often does not participate, even when a group or activity requests participation. Ignores or does not see connections between daily work and overall course concepts.

F: Acts in a manner that disrupts the learning of self and others. Creates an uncomfortable environment for others (disrespect, incivility, etc.)

![]()

This journal is connected to English 099 Learning Outcome #3: At the end of the course, students will demonstrate responsibility for their own learning including attending class, completing required work, identifying what they do not know, and framing useful questions to help them move forward.

Journal adapted from the blog entry "Grading Classroom Participation Rhetorically" by Ryan Cordell. Professor Hacker, 6 Oct. 2010.

Appendix B

Learning Journal: Letter to a Future English 099/101 Student

Assignment: Write a letter to next semester’s ENGL 099/101 students offering them advice on how to succeed in the course. Write this learning journal entry as a letter, complete with a greeting (like “Dear Incoming Student”) and a sign-off (like “Sincerely”).

Keep your audience in mind as you write. Remember, the purpose of this letter is to offer advice to incoming students. Focus on what might be helpful to a new student who doesn’t necessarily know you personally. Use your experiences as specific examples to support your suggestions.

Context: What advice might be helpful to next semester’s English 099/101 students as they begin these courses? What have you learned this semester in English 099/101? As you prepare to draft your letter, think about the following ideas, and then figure out how you can use your knowledge to give next semester’s students useful tips. Ask yourself:

- What have I learned about myself as a learner, a writer, and a student?

- What learning or writing tasks did I respond to most easily?

- What learning or writing tasks gave me the greatest difficulty? How did I overcome these challenges?

- What was the most significant thing that happened to me as a learner, a writer, or a student?

- What do I feel proudest about regarding my learning and my writing?

- What do I feel most dissatisfied with regarding my learning and writing?

- What do I wish I knew on day one that I know now?

- What questions remain for me even at the end of the semester?

![]()

This journal is connected to all of the English 099 Learning Outcomes.

Prompts adapted from Zubizarreta, John. The Learning Portfolio: Reflective Practice for Improving Student Learning. U of Wisconsin Stout. Web.

Appendix C

Survey of Student Attitudes about Writing and Learning

For numbers 1-7, choose one: Strongly Agree; Agree; Neutral; Disagree; Strongly Disagree

- Other people influence the quality of my writing. LO5

- I am confident that I can correctly cite sources in my writing. LO1

- I am confident that I can correctly follow the rules for language conventions (grammar, spelling, punctuation, usage). LO1

- I am solely responsible for the quality of my writing projects. LO3

- Working with others helps me complete writing projects. LO5

- I am a good reader and writer.

- Taking ENGL 099 is a valuable opportunity to help me improve my writing.

For numbers 8-16, choose one: Always; Usually; Sometimes; Rarely; Never

- Before I begin a writing project, I think about how best to proceed. LO2

- I prefer to break a writing project down into small parts to help me complete it. LO2

- I prefer to complete more than one draft of my writing before I submit it. LO4

- I prefer to proofread my writing before I submit it. LO4

- I prefer to use computers for drafting and revising essays.

- I enjoy reading when I can choose what I read.

- When I am assigned something to read for class, I complete it. LO3

- I ask questions if I am struggling with a reading or writing assignment. LO3

- When I face an obstacle that will affect my performance in class, I seek solutions to help me. LO3

Miscellaneous Response Types

- In total, I work _____ hours per week.

- hrs/week; 6-10 hrs/week; 11-15 hrs/week; 16-20 hrs/week; 21+ hrs/week

- In high school, my grades in English classes were usually: As; Bs; Cs; Ds; Fs; don’t know or N/A

- My high school GPA was 4.0 or higher; 3.9-3.0; 2.9-2.0; 1.9-1.0; 0.9-0.0; don’t know or N/A

- At least one person in my immediate family (parents and/or siblings) graduated from college. Yes; No

- I am currently taking OR have already taken GENS 105. Yes; No

Cho, Sung- Woo, et al. "New Evidence of Success for Community College Remedial English Students: Tracking the Outcomes of Students in the Accelerated Learning Program (ALP)." Dec. 2012. Community College Research Center. Web. 15 Mar. 2016.

Coleman, Dawn. Replicating the Accelerated Learning Program: Preliminary but Promising Findings. Center for Applied Research. 2014. Center for Applied Research. Web. 10 Mar. 2016.

Connors, Robert J., and Andrea A. Lunsford. "Frequency of Formal Errors in Current College Writing, or Ma and Pa Kettle Do Research." College Composition and Communication 39.4 (1988): 395-409. National Council of Teachers of English. Web. 29 Jan. 2016.

Cordell, Ryan. "Grading Classroom Participation Rhetorically. "Prof Hacker, Oct. 2010, The Chronicle of Higher Education. Web. 18 Jan. 2017.

Cox, Rebecca D. The College Fear Factor: How Students and Professors Misunderstand One Another. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. 2009. Print.

Downing, Skip. On Course: Strategies for Creating Success in College and in Life. 7th ed. Boston: Wadsworth, 2013. Print.

Dweck, Carol S. "Growth Mindset, Revisited." Education Week 23 Sept. 2015, Commentary. EdWeek. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.

---. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random, 2006. Print.

"Features of ALP Responsible for Its Success." Accelerated Learning Program. Community College of Baltimore County, n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2016.

Fink, L. Dee. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003. Print.

Hern, Katie. Exponential Attrition and the Promise of Acceleration In Developmental English and Math. 2010. The RP Group. Web. 15 Mar. 2016.

Johnson, Roy Ivan. "The Persistency of Error in English Composition." School Review 25 (Oct. 1917): 555-80. Print.

McKusick, Donna, et al. "Lessons Learned from Five Years of Developmental Education Acceleration." Achieving the Dream Annual Institute on Student Success. Anaheim, California. 6 Feb. 2013. Community College Research Center. Web. 10 Mar. 2016.

Orsini-Jones, Marina. "Troublesome Language Knowledge: Identifying Threshold Concepts in Grammar Learning." Threshold Concepts Within the Disciplines. Ed. Rey Land, Jan H. F. Meyer, and Jan Smith. Rotterdam: Sense, 2008. 213-26. Print.

Perkins, David. "Constructivism and Troublesome Knowledge." 2006. Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge. Ed. Jan H. F. Meyer and Rey Land. London: Routledge Falmer, 2006. 33-47. Print.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. "Transfer of Learning." International Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Pergamon, 1992. 1-13. CiteSeerX. Web. 8 Feb. 2016.

Robertson, Liane, Kara Taczak, and Kathleen Blake Yancey. "Notes toward A Theory of Prior Knowledge and Its Role in College Composers’ Transfer of Knowledge and Practice." Composition Forum 26 (2012): N.p. Web. 28 Jan. 2016.

"TYCA White Paper on Developmental Education Reforms." Teaching English in the Two-Year College 42.3 (2015): 227-43. Print.

Wiggins, Grant P. Educative Assessment: Designing Assessments to Inform and Improve Student Performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998. Print.

Witty, Paul A., and Roberta La Brant Green. "Composition Errors of College Students." English Journal 19 (May 1930): 388-93. Print.

Zubizarreta, John. "The Learning Portfolio: Reflective Practice for Improving Student Learning." University of Wisconsin Stout School of Education. Web. 18 Jan. 2016.

Stephanie Kratz

Stephanie Kratz is a Professor of English (composition and literature) and the former Coordinator of English 099 at Heartland Community College in Normal, Illinois.

The Basic Writing e-Journal Issue 14.1 https://bwe.ccny.cuny.edu