Synesthetic White Noise:

Translating, Transforming, and Transmitting Affect/Text

Daniel Wuebben

ABSTRACT: Wuebben describes a multimodal writing project that he used in an adult oriented college literature course in New York City. Students were asked to read and interpret several novels, including White Noise by Don DeLillo--the focus of this essay. Moving out of the classroom and into their lower Manhattan Wall Street neighborhood, adult undergraduates experiemented with YouTube, hand-held video cameras, and cell phone recordings to depict scenes similar to those in White Noise. Wuebben concludes that students benefitted from participating in the project: it enhanced their interest in the novel, introduced non-traditional forms of literary interpretation, and challenged students to experiment with video recording as an approach to interpreting literature.

Multimodal writing assignments can draw basic writers beyond the printed page and help them to develop technology literacy. Ideally, these lessons also help students to develop academic literacy. For example, Jeff Horwitz, a second grade teacher in St. Louis, Missouri,introduces his students to Flip Video cameras and asks them to create “tutorials” for their fellow classmates. Student tutorials often cover basic tasks such as building a model airplane or making a grilled cheese sandwich. The students gain the confidence and the technological skills required to connect with their peers both in the classroom and on the web. The exercise also introduces these young writers to the ideas of narrator and audience and that, in turn, prepares them for future writing assignments. This is “show and tell” for the twenty-first century.

Basic writing skills are taught with and through multiple modes at the college level as well. Stafford Gregoire of LaGuardia Community College introduces students to the essay-writing process by having them create and critique thesis statements in the form of PowerPoint slides.The students see arguments unfold in a series of slides containing images juxtaposed with text. By privileging the textual—but not isolating text—these basic writers do more than develop PowerPoint skills; they develop writing skills. More specifically, these students are able to “overcome resistance to revision and reflections of preliminary drafts” (Gregoire 4).

These types of considerate, structured multimodal assignments embody new directions in instructional design and the pedagogical influence of digital media and social networking. PowerPoint presentations, instructional videos, photo-sharing sites, and blog posts can engage traditional aspects of the writing process such as planning, drafting, editing, and revision. However, these new media do not look like what is traditionally considered “writing.” In the relatively new, open, and fast-moving multimodal writing environment, one wonders how a printed response paper might be assigned and assessed compared to a blog comment, or how an eight-page research essay might achieve different course objectives or learning outcomes than a wiki contribution or a PowerPoint presentation. In short, multimodal compositions are reshaping writerly roles and pedagogical goals—and most of us feel like we are scrambling just to keep up.

This essay recounts my personal and pedagogical “scrambling.” It charts my resistance to teaching with technology, and then describes a tech-heavy, multimodal writing project that I designed for a group of students enrolled in a mid-level literature course. It was not a basic writing course, but many of the students (though not all) shared some of the same challenges as students who are often placed in basic writing courses. They struggled with reading critically, citing evidence, and writing longer essays. To help students overcome these challenges, I designed a lesson plan that involved free writing, video cameras, and voiceovers. We used multimodal writing to transform and transmit Don DeLillo’s novel White Noise into a short video, White Noise in NYC.

Technology Baby Steps

When I began teaching, I viewed technology as a distraction. I was skeptical about the value and reliability of course management systems like Blackboard. I preferred blue books to blogs, stapled pieces of paper to PDFs. I would not accept a writing assignment if it was not printed on 8 1/2 x 11. I shied away from communicating with students over email. Twitter and Facebook made my head spin. Students could become familiar with “killer apps” and the subtleties of the latest SMS jargon on their own time, but (insert belligerent tone) “Not in my class!” The complexities with and between traditional and print-based literacies and digital and technological literacies seemed bewildering. I worried that teaching with technology and through multiple modes might dismiss the pleasure of reading books and undermine the power of the printed word. I had a hard time navigating the tumultuous seas of media, genre, and epistemology. I harbored fears that if I brought technology into the classroom, we would all become unmoored.

Around the beginning of my third year of teaching composition classes at various colleges within the City University of New York, I began to reconsider the use of technology in the classroom. This did not happen overnight, but the turning point may have been a conversation with a colleague who had created a blog and was using it to post readings and hold discussions outside of class. I thought a blog would likely disorient students and might undermine what little authority I (as a young part-time instructor) felt I had in the first-year composition classroom. My colleague looked at me sternly and warned, “If you don’t use technology, it will use you.” In that moment, my fear of being lost in a sea of applications and gadgets was dwarfed by the fear of being left behind altogether. I realized that if I remained resistant, I would drown in the digital waves sweeping through higher education.

The following semester I started to take technology baby steps—posting readings to Blackboard, creating a free blog on Wordpress.com, and supplementing lectures with PowerPoint presentations. While these experiments achieved varying levels of success, I often felt like I was using technology just to be using technology. I rarely felt that a new sense of potency or creativity had erased or even adequately eased my sense of being overwhelmed or scrambled.

Looking back, I realize that I had mistakenly assumed that students would be eager to abandon typed assignments and my messy notes on the chalkboard. I thought that they were eager to race towards the technological frontiers of digital projectors, hypertext readings, and class weblogs. To my surprise, many of my students shared my ambivalence towards technology. We generally agreed that working with new technologies and writing in new modes could spice up the course material, offer new outlets for personal expression, and, ideally, advance our careers; however, most of us still felt that something was missing.

Multimodality as Synesthetic

One thing that often seems to be missing when we read/write with technology and multiple modalities is the fluid exchange of feelings. On the surface, this seems contradictory, because multimodal texts—by which I mean texts that use a combination of visual, auditory, and orthographic signs—have the power to stimulate different senses (sight, hearing, touch, and, in the most creative cases, taste and smell). However, some multimodal texts, such as those presented in PowerPoint, can lose valuable content or interesting arguments because of glitzy transitions or percolating fuchsia borders. A multimodal PowerPoint presentation can appear to hide a weak argument or flat content. Furthermore, a multimodal text with hyperlinks (the embedded image) can disrupt a reader’s attention.

Students need to develop literacy with multimodal texts and to understand how these texts can enhance and sometimes interrupt the reading experience. Therefore, I ask students to think about the affect of images, symbols, videos, or sound bites embedded in a text. “What icon might be pasted alongside the sentiments expressed in this paragraph?” “How does it feel to tap a Kindle page rather than turn the pages of a printed book?” “How does a handwritten birthday card elicit different feelings than a wall post on a Facebook profile?” “What kind of odor does this article seem to emit?”

These questions underlie what I offer as my pop-psychological and pseudo-scientific thesis: Developing multimodal literacy is like developing synesthesia.

Synesthesia is a condition in which two normally independent qualia merge together as if the wires in the brain had been temporarily crossed and then permanently spliced together. A common form of synesthete attaches a specific color to a specific number (e.g., 33 is green, 7 is red). The neuroscientists V.S. Ramachandran and E.M. Hubbard define synesthesia as “a curious condition in which an otherwise normal person experiences sensations in one sensory modality when a second modality is stimulated” (4). When an “otherwise normal person” reads text, that person is often stimulated in other modalities. Reading is not just about seeing. Literature, especially when performed with more than words (images, hyperlinks, video), seems designed to stimulate one or more “modalities” at the same time. “I am sensitive reader,” I tell my students. "Smelling books, feeling sentences, or tasting words slide off the tongue is not excessively abnormal!”

Synesthesia provides a psychological link between the common feelings of being stimulated—even overwhelmed—by different modes of information and the numerous possibilities of the multimodal text. I admit that my thesis is not scientific: the relationship between synesthesia and multimodal composition must be further grounded in psychology and neuroscience.1 Future studies might investigate the relative benefits of visualizing arguments in terms of certain colors or numbers, brainstorming the shapes of certain search terms, or taking something that was composed on a word processor and giving it a distinct smell. In the meantime, humanities scholars will continue theorizing how literary texts stimulate and affect. For example, in his study of John Edgar Wideman’s “funky” novels, Stephen Casmier argues that “odors exude ideology” (191). If smelling provides a pathway to understanding an ideological position, how might our students further read and write with their noses instead of solely composing with their eyes and hands? Why not ask students to read and write with all five senses? What can we gain by foregrounding the pluralism of sensory perception and thus delimiting the affect of multimodal texts and the impression they make in the classroom and beyond?

In response to these questions and in an attempt to clarify what I mean by the “synesthetic effect” of multimodal writing, I will describe and analyze a classroom project that involved students in reading Don Dellilo’s White Noise and then translating, transforming, and transmitting the text. Here, briefly, is how it worked: At the beginning of a particular class meeting, I asked students to choose a part of DeLillo’s text that had impressed them and then to write short responses. After that, students formed groups and went outside of our classroom to find images from the novel and reenact a few scenes. The students recorded these images and reenactments on handheld cameras. Next, we dubbed over the video recordings with voiceovers made by students reading from Delillo’s novel. Finally, students made slight edits to the audio and video to create a “whole” writing project. As a group, the students did the work of translating, transforming, and transmitting between texts and images, genres and writers, composition and film. By the end of this project, the students thought in (and with) new modes and those with different learning styles found a new possibility for expressing their thoughts (which is, after all, one of the primary functions of the writing course).

Precursors to a Synesthetic, Multimodal Project at the Center for Worker Education

Between 2005 and 2010, I had the pleasure of teaching as an adjunct instructor at the City College of New York's Center for Worker Education (CWE). This division of City College is positioned on the seventh floor of a building deep in the Financial District. It is a few steps from Wall Street and Battery Park and some classrooms feature views of the Statue of Liberty.

Most CWE students are adults with families and full-time jobs. The students are generally mature, responsible, and hard-working. They often tell themselves, “This time I’m going to get it right!” and then take on intense pressure to succeed. After years of separation from the classroom, many CWE students feel limited by their lack of academic language and composition skills. In my experience, these students are relatively quick to adopt critical thinking skills, and their rich life lessons can help them to understand the value a strong argument. However, because basic writing or entry level composition classes are not offered at CWE, students lacking academic literacy skills must develop these skills in more content-heavy courses. For those who are nervous about the writing process, taking classes that meet one night a week for three hours can further complicate matters. In a course with such a limited number of meetings, each lecture and due date is critical.

In addition to these writing challenges, students often had difficulty reading longer and more complex arguments. It was not uncommon for students to raise their hands in class and then state that they had done the reading but “just didn’t get it.” Many of these adult learners became frustrated with the author (and sometimes with the professor) if he or she did not come straight to the point. Conversely, many of the same students I encountered felt unprepared to write a thesis statement about an ambiguous issue, and especially about a postmodern novel.

These tensions between author, student, and teacher became more apparent during my first semester teaching American Literature after World War II. Other than the historical parameters, I was given license to design the curriculum as I saw fit. I chose seven novels that I considered both engaging and representative: John Edgar Wideman’s Philadelphia Fire, Marilyn Robinson’s House Keeping, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Phillip Roth’s The Human Stain, Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses, Sandra Ciscernos’s House on Mango Street, and Don DeLillo’s White Noise. American Literature was listed as an elective course, but the roster included a number of students who were still building academic literacies. My core goal remained the same: I wanted each student to read each novel and to write some type of critical response.

As I was preparing for that semester, I was invited to participate in a workshop being held by the City College (CCNY) Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL). The workshop addressed the possibilities for using “Flip Videos” in the classroom; afterwards, the director of the CETL informed us that he had cameras which could be loaned out for class projects. I began thinking of how I might use these video cameras for the American Literature class. Around this same time, I began re-reading Don DeLillo’s White Noise.

In previous readings of the novel, I had been drawn to the narrator, Jack, and his development of Hitler Studies and his wife, Babette, who becomes addicted to Dylar, the déjà vu inducing happy pill. This time I was struck by some of the cinematic landscapes: the “most photographed barn in America,” (12) the expressway beyond the backyard with its sparse traffic, and the ephemeral supermarket aisles filled with attention-grabbing plastic products. Drawing together my newly developed familiarity with these easy-to-use cameras and my new view of Delillo’s story, I began to imagine a different way for students to engage the novel and to see (or re-see) what is printed on its pages.

With adequate support for integrating technology into the classroom and a story that seemed to encourage multimodal interpretation, I soon set the stage for a translation of White Noise (that eventually turned into a transformation and transmission of White Noise). I borrowed two cameras from the CETL, a third digital video camera from a friend, and asked a student in my class to bring a fourth. The night before our class meeting I sent an email to the entire class in order to prepare them for the project. I also explained that this would be assessed as an informal writing assignment, and students who did not want to be on camera (for whatever reason) could find other ways to participate without any adverse effect on their grades. The next night, I brought to class two laptops—my personal device and another on loan from CWE. Both laptops were outfitted with voice recording and video editing software. I had never used these programs before, and so I solicited two tech-savvy students to assist. (This brings up a good rule of thumb for multimodal composition: students can/should help professors that are unfamiliar with more recent media or technologies.)

Translating White Noise

…translating their own writing into images and critiquing those ‘multimodal texts’ offers an opportunity to teach…

--Stafford Gregoire

On the evening of this multimodal event, I asked each student to select from De Lillo's text a passage that contributes to the broader issues proposed in the novel ( “the cemetery” and death“ the supermarket” and consumerism, etc.). Then, I asked the students to copy their selected passages onto paper and free-write for fifteen minutes about the ideas or feelings evoked by these particular scenes or landscapes.2 So far, the project seemed similar to many basic writing exercises: students were sitting quietly while copying down a “prompt” and then offering their reactions. These students were actually translating the text. Translation is not only a matter of converting a text from one language to another—it also means converting between two mediums. By transcribing a passage from DeLillo’s novel, they were translating the “book” medium into something different and slightly more personal.

When the fifteen minutes passed, I asked for volunteers to read out loud the quotes they had chosen to transcribe/translate. I wrote between ten and fifteen key phrases from the quotes along with page numbers on the board. Then, I guided an informal discussion about the issues at stake in the words and phrases DeLillo uses such as “waves and radiation” or “tourism.” After this short discussion, I asked the class to form groups and for each group to choose one of the quotations on the board. Rather than talking about a quote, students were asked to think of ways to film it.

Transforming White Noise

More is to be gained from analyzing the transformations that occur when ideas change creative context and encounter fresh readers.

--Gillian Beer

Gillian Beer’s Open Fields: Science in Cultural Encounter includes a chapter titled, “Translation or Transformation? The Relations of Literature and Science.” In this chapter, Beer explores some of the powerful interchanges between scientific language and literary genres from the nineteenth century to argue that when science appears in literature and vice versa, the exchange goes beyond “translation” of ideas to become a “transformation” of ideas. For example, Beer observes that poetry was the authoritative mode of discourse in the nineteenth century and therefore scientists such as “James Clerk Maxwell and Charles Lyell habitually seamed their sentences with literary allusion” (174). Later in the chapter, she situates her argument in a more recent production, DeLillo’s White Noise: “What, we may ask, does science contribute to this work?” (Beer 188). In her response, Beer states:

The society imagined [in White Noise] is, moreover, one whose deepest disquiets are the outward ripples of fundamental scientific theory, particularly the insistence on entropy, on increasing disorganization, and the simultaneous life and death of space-time phenomenology. The novel refuses decisive features, closures, is punctuated by the barren poetry of overheard utterances from radio and television shorn of context. (188)

In DeLillo’s novel, scientific theories and scientific language not only translate everyday (and not so everyday) events; they transform them. Science is an active agent, shaping the way the characters understand (or mis-understand, as the case often is). Science, technology, and the “waves and radiation” through which they intersect underpin the plot. By asking students to “transform” the novel and thereby actively placing it in a “new creative context,” I was inviting them to engage and, hopefully, appreciate the transformations that can take place between science and literature.

Students took a “scientific” text, which was “shorn of context,” and used it as inspiration to recontextualize their environment. Armed with cameras and a few creative ideas, they headed outside the classroom as inquisitive and energetic learners. Some went even further, transforming lower Broadway into their stage.

Figure 1. First shot from the student film, “White Noise in NYC.”

Each group was given the same prompt: capture a few images or recreate a scene and capture it on video. An especially boisterous group returned with footage of bold volunteers lying on the sidewalk, reenacting the passage from White Noise when the town rehearses a response to a widespread catastrophe. Another group went into a nearby Duane Reade pharmacy and captured the colorful plastic products lining the aisles as well as a shot of the television monitor on the ceiling, which shows the store’s surveillance tape. One student marched the half-mile up to Ground Zero and captured heavy equipment, flashing lights, and men in neon green suits and hard hats. From our classroom window, someone shot the traffic flowing in and out of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and, from a separate window of our 7th Floor campus on 25 Broadway, someone else recorded a ferry passing across the Hudson Bay with the Statue of Liberty in the background. One of the students captured the flashing sirens of a Con Edison utility truck and happened to record an interesting exchange in the process: We hear a woman, presumably a Con Edison employee, ask him what he is doing. She then somewhat confrontationally says, “Because my supervisor is inside.” The student, continuing to record, politely replies: “No, no, it’s for a school project. Tell your supervisor it’s for a school project.”2

Sayid, one of the stars of the short film—we see him making a withdrawal from the ATM machine—later said that he did not feel that reading DeLillo’s novel was “satisfying” in itself. However, he added, “The project of making a video that translated the text was a fun process…put the themes and ideas of the novel into a cleverly relevant context.” After an hour, we had a rich and dizzying collection of footage, most of it shaky and rather unprofessional camerawork but all of it, in its own way, a perfect reflection of what Beer calls the “increasing disorganization” felt by DeLillo’s characters and the “barren poetry of overheard utterances” spread throughout the narrative (188). Transforming text allowed these writers to engage with the story and our environment. Making the video helped to capture the attention of students who might have otherwise been transient. The words on the page were being transformed into action, their individual responses transformed into a collective perception, which is another one of the major themes presented in the novel and which is further touched upon below.

When everyone returned, the students downloaded and edited the texts they had just translated and transformed. One student plugged the cameras into the laptop and began arranging the clips. Meanwhile, six students volunteered to read aloud the passages from DeLillo’s novel into a voice recorder. They lined up, each holding a copy of White Noise. When the voiceover recording equipment was ready, the students approached the microphone and recited the lines. Reading the quotes took a little over four minutes. To keep things simple, we decided to cut and rearrange the video footage into four minutes of visuals and then reinsert the voiceover. By the end of a three-hour class session, they had the rough draft of a translation/transformation, which they decided to title “White Noise in NYC.”

The result was a multimodal composition. It was a combination of the passages students had translated by hand, ideas they had gleaned from DeLillo’s work, and the images and landscapes they confronted on a daily basis. I will be the first to admit that our project was made possible by fortunate circumstances: freedom with my curriculum, institutional support in the form of technology, and, the intangible—enthusiastic student participation. In the future, it would be interesting to see if the same project might help students to engage other visually stimulating novels such as Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. It might also be helpful to have students build upon their translation/transformation by composing high-stakes essays that incorporate other critical responses to the novel or to reflect on the modes of popular discourse (novels, online articles, YouTube videos, etc.).

Our multimodal composition was more like a low-stakes, in-class writing assignment, but it was a work of composition that required students to analyze text, select quotes, compose, and edit. As a whole, it provided an effective way to have the students “write” to learn. M.C., another active participant reflected:

This experience was heightened because of time constraints & bad weather. It was great sharing with my peers my interpretation of a small section of the text. It was as close as talking without words that I've come to.

The final production (a series of video images dubbed over with readings of the text) provided a chance for students to talk without words. They talked with DeLillo’s words but also with our environment. They made quick connections between DeLillo’s novel about suburban America and their experience of living and working in New York City.

The students’ connections between themes, text, and video also fulfill the types of thinking encouraged by literary criticism. More specifically, this project could be used to underscore the relationship between novels and their film adaptations. In an article recently published by the PMLA, Ian Balfour outlines some of the ways that English professors “might teach film and literature sometimes with and against each other” (969). For example, Balfour argues, “a cinematic adaptation can function as a compelling supplement to its literary source” (971). His primary example of such teaching methods is offered through an analysis of Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining. The modest translation/transformation of White Noise does not begin to approach the genius of Kubrick, but as Balfour says of Kubrick’s adaptation of King, the video could “constitute and even perform striking analogues to the rhetoric, themes, and narration of …[DeLillo’s] text” (Balfour 971). Students were making arguments about how DeLillo’s text related to their own lives while simultaneously questioning the traditional act of composition.

Transmitting Text/Affect

am using the term ‘transmission of affect’ to capture a process that is social in origin but biological and physical in effect.

--Teresa Brennan, The Transmission of Affect

Many college classes follow a linear model of transmission: a teacher lectures or sends the message and the students listen and (hopefully) receive the message. The student plays a passive role, producing writing that attempts to re-transmit the professor’s message. Assignments like the “White Noise in NYC” video break down this linear model of transmission. By uploading their collectively composed text to YouTube, these students participated in what has become a powerful way to write for a public audience. In addition, by translating/ transforming/transmitting the text, they also enhanced the affective quality of their learning experience.

The short video does not replace the novel, but it does create a platform from which to view the novel in a new light. For example, over a year after the project was completed, I sent emails to each of the students involved and asked them what they remembered about the experience. They remembered the video as a chilling reminder of the novel’s themes. Mary (who can be heard reading the passage about the ATM) said that making the video and watching it again reminded her how much she relies on cell phones, bar codes, and ATMs “without giving it a second thought.” The project helped her to reflect, to have “second thoughts.” By filming things that often escaped attention, she acknowledged the limits and the possibilities of attention. By disrupting the normal writing process and activating multiple senses, students improved their understanding of the novel and their experiences with technology.

Overall, Mary felt that the video was still “a great reflection on the book. . . . With all the immediate access to things that improved technology brings us, we haven’t fried yet! And I don’t think the government is tracking me. Yet.” Mary’s comment shows a distinction between the personal and “immediate” experience of technology and the invisible forces that seem to pervade our lives. Another student was also affected by reviewing the ATM scene:

The words ‘Tormented arithmetic’ and the ‘system’ remind me of the time when I was hell bent on not having an ATM card but was slowly sucked into having one and, then, enjoying the convenience of having one (sucked into the system). The arithmetic to me are the account and routing numbers on top of remembering a pin number. Sometimes, it’s too much but the system is something that is hard to get away from especially in NYC. All you have to do is swipe your debit card or credit card and in 123 you’ve made your purchase. It’s a wonderful, damaging experience.

Kaylah seemed to have the same sense of being overwhelmed that first made me shy away from bringing technology into classroom: it can be “too much.” Kaylah’s comments also reminded me that the ease with which technology allows all of us to do things like make purchases by debit card can also be unsettling. This does not mean that how, where, and why we engage technology should be ignored. If anything, this ambiguity asks us to reexamine our relationships to technologies we use every day.

This assignment provided one such form of reexamination. As a group, we learned about art and literature by engaging in the process of the translating, transforming, and transmitting of text. Whether transcribing by hand or capturing on video, the students had to think about what constitutes effective writing and good storytelling. Through translation, transformation, and transmission of a text, they also found themselves reflecting on the power of printed text, transcribed notes, voice recordings, and the numerous other modalities and technologies which they engage on a daily basis.

Synesthetic Whirlpools

The final video was not of professional quality, but the writing project was a success. A year later many students recalled themes from the book and certain characters and passages. The experience produced strong associations between the images caught on tape, the ambiguous feelings produced by reflecting on technology practices, and specific passages of DeLillo’s novel. These associations border on the synesthetic because they link orthographic text to a particular event, a series of voices to a series of images. The goal of inviting students to develop this peculiar “psychological condition” was to show them how engaging multiple modes can help to translate, transform, and transmit their ideas and to possibly activate certain affective responses in readers.

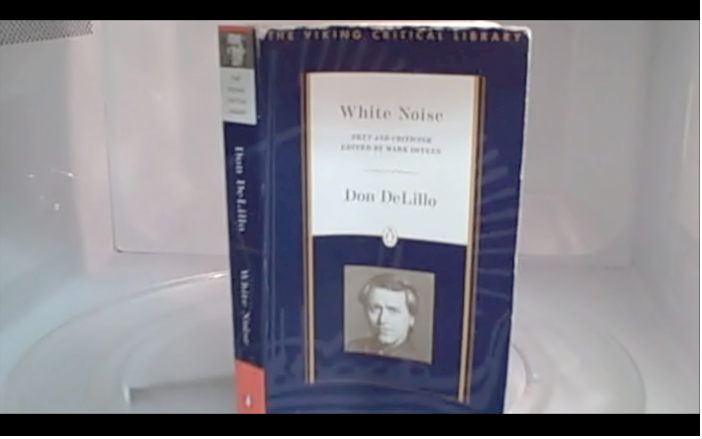

Separate from the positive student responses, two specific clips caught my eye when I reviewed the video. In the opening, The Viking Critical Edition of White Noise with DeLillo’s headshot trimmed in blue is seen standing upright inside a microwave. J.M. directs the action and says “Go,” at which point we hear and then see the microwave door slam shut. In diagetic space, the book will soon begin to “cook” through the “waves and radiation” of the machine. After the door closes, we can barely see the blue book encased in the plastic box. The shot is instead dominated by the reflection of the microwave door. In that reflection, we see the hand-held camera and two students capturing the moment. Of course, the camera itself cannot capture the waves and radiation that will soon be emitted by the buzzing microwave.

Figure 2. Frame from “White Noise in NYC”

Another eerily provocative moment occurs in one of the final shots of our film. The Statue of Liberty can be seen in distance. Two buildings, one of which has a blue tarp covering a window like a band-aid on its ribs, frame the Hudson Bay. A student downloaded a robot voice program from the Internet to read the following passage from DeLillo’s text:

Being here is a kind of spiritual surrender. We see only what the others see.The thousands who were here in the past, those who will come in the future. We've agreed to be part of a collective perception. It literally colors our vision. A religious experience in a way, like all tourism.

In the novel, “being here” is standing in front of “the most photographed barn in America,” (12) a site where the excitable professor of Americana, Murray, brings the quirky but strangely calm professor of Hitler Studies, Jack. In the student version, the most photographed barn in America is translated into one of the most photographed statues on the planet. The idea that “we see what the others see” is transformed: Murray’s statement seems even more political, inflected by the historical and ideological weight of the statue and the nearby Ellis Island (which is obscured by the building on the right). The ferry passing from right to left alerts us that time is passing, and again, the reflective glare from the window suggests that the viewer is being viewed, the reader is composing, the novel, the buildings, and the ideological underpinnings of such a patriotic icon are all coloring our vision as strongly as the green rust has covered lady liberty.

At this point, in my mind, the doubling produced by the translating/transforming/and transmitting gives way to a wave of stimulants and the linear narrative supported by my theoretical dialectic breaks down. The text seems to radiate: the green tablet etched with the date of Independence smells like a toxic cloud; the earthy-colored copper sheets seem to ring like a bell, the torch feels like a warm sip of Scotch, her entire body quivers, my memory of the 25 Broadway building looks like a wave sweeping into the Atlantic opening a new set of relations between myself, DeLillo’s novel, and the environment in which we continue to live, work, and learn.

Author's Note

I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to all of the writers/film-makers/multimodal composers enrolled in this class. Without you this project and this essay would not have been possible. On behalf of this class, I would also like to give special thanks to Jon Gray. Jon was a gifted writer. He brought insight, creativity, and humor to the CWE community. He will be missed.

Notes

1. It would be especially interesting to read composition theory through the recent neuroscientific understanding of synesthesia as espoused in Richard Cytowic’s popular studies, The Man Who Tasted Shapes and Wednesday is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia.

2. After the project was complete, and before uploading the video to YouTube, I obtained written consent from each student. This consent covered use of each student's image for the purposes of the video. Months later, a few students submitted their reflections on the project. Each of these students gave a separate consent to have their writing used in my essay. Their names have been changed to protect their identities.

Works Cited

American Literature Class at the CCNY Center for Worker Education. "White Noise in NYC." YouTube.com. 29 April 2009. Web. 7 Nov. 2011.

Balfour, Ian. "Adapting to the Image and Resisting It: On Filming Literature and a Possible World for Literary Studies. PMLA. 125.4 (2010):968-976. Print.

Beer, Gillian. Open Fields: Science in Cultural Encounter. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. Print.

Brennan, Teresa. The Transmission of Affect. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004. Print.

Casmier, Stephen. “The Funky Novels of John Edgar Wideman: Odor and Ideology in Rueben,

Philadelphia Fire, and The Cattle Killing.” Critical Essays on John Edgar Wideman. Eds.

Bonnie TuSmith and Keith Eldon Byerman. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press,

2006. Print.

Cytowic, Richard. The Man Who Tasted Shapes. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. Print.

---. Wednesday Is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia. Cambridge: MIT Press,

2011. Print.

Delillo, Don. White Noise. New York: Viking Press, 1985. Print.

Gregoire, Stafford. “PowerPoint Reflection and Re-Visioning in Teaching Composition.” BWe:

Basic Writing e-Journal. 8.1/9.1 (2009-2010): 1-10. Web. 5 January 2011.

Ramachandran, V. S. and Hubbard, E. M. “Synaesthesia: A Window into Perception, Thought

and Language.” Journal of Consciousness Studies. 8.12 (2001): 3-34. Print.

Dan Wuebben

Dan Wuebben is a Lecturer in the Writing Program at the University of California Santa Barbara.